The fight over building the Canadian-owned and operated LNG pipeline across lands from Klamath County to Coos Bay has spanned several years now. LWV Klamath County has been involved as one of the 4 local leagues that has worked to support environmental and land rights across the projected pipeline route.

Here are several updates and recent media reports on this project, which has remained stalled over legal permits for a long time.

From ProPublica:

This past spring, while much of the country focused on COVID-19, three men who work in an obscure corner of the federal government weighed a question with profound effects across the American West. On the docket was a proposal to build a natural gas pipeline that would slice through hundreds of miles of Oregon wilderness, private lands and areas sacred to American Indians. The plan, which had been repeatedly rejected by state and federal regulators for more than a decade, would give a Canadian company the right to seize the land it needed from any American property owner who stood in the way. The government panel that would make the decision can meet in person. But on this March afternoon, it was conducting the people’s business in writing — government by what amounts to dueling memos.

(read more)

From Capital Press: Empowering Producers of Food and Fiber:

COOS BAY, Ore. — Wind howls across the channel — the kind of wind that turns umbrellas inside-out. On the water, the ghost-like outline of a ship, scarcely visible through white fog and driving rain, seems to stand still.

It is here the Oregon International Port of Coos Bay has proposed the largest project in its history: expanding the channel to 45 feet deep and 450 feet wide and allowing the port to take its place among the international shipping giants along the West Coast.

People have been talking about the idea for decades. Advocates say it could open new avenues for international trade of agricultural goods and transform the region’s economy.

(read more)

dated October 12, 2020: Western Environmental Law Center:

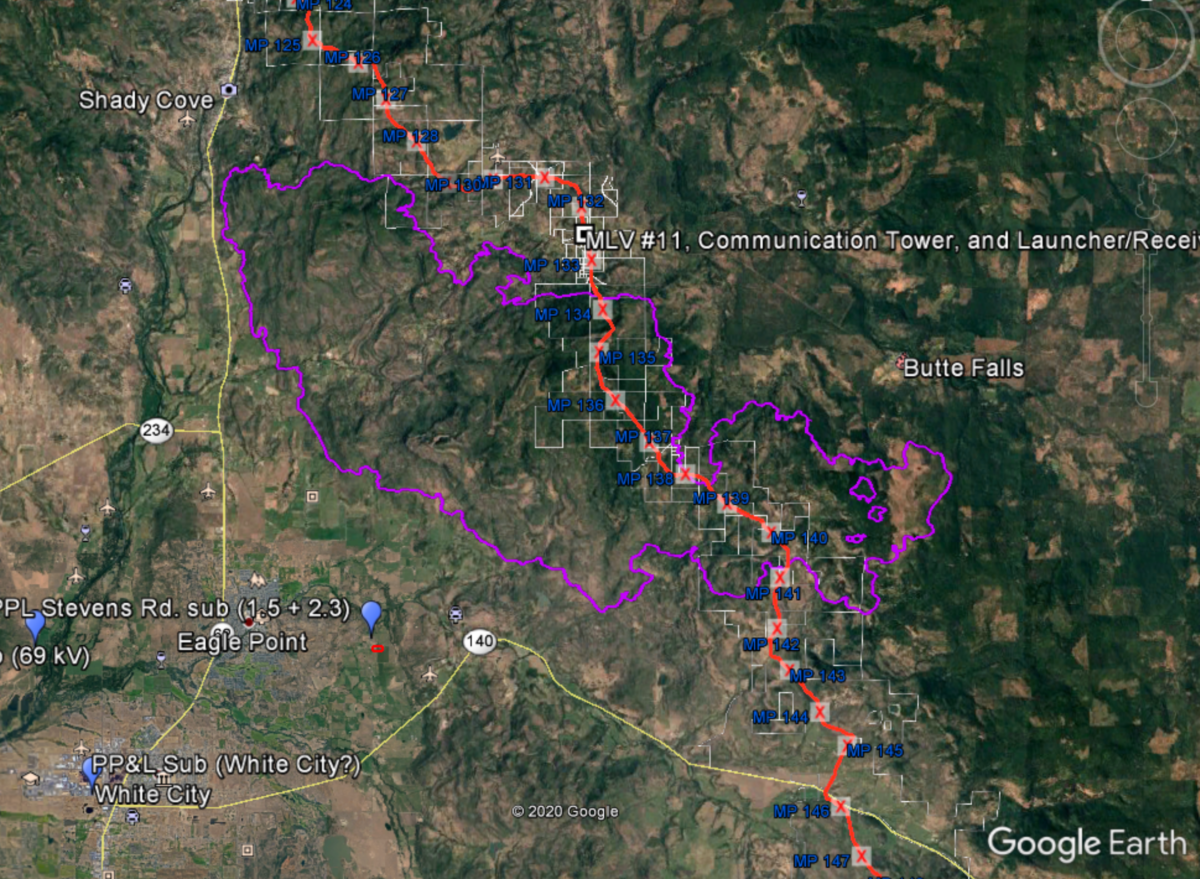

WELC (Western Environmental Law Center) is a critical ally in the fight against the Jordan Cove LNG and Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline project (JC/PC). They recently made a formal request for a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS), due to factors associated with the South Obenchain Fire. The fire burned 32,000 acres, including 7 miles of the proposed pipeline route. (Map and request attached.)

Here’s how WELC’s request starts:

We write to bring to your attention significant new information requiring supplementation of existing environmental analysis for the Jordan Cove Energy Project since the FEIS was released in November 2019, and FERC’s issuance of the Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity in March 2020. Western Oregon is experiencing an unprecedented wildfire season. Oregon Governor Brown has declared a state of emergency, calling the wildfires a “once-in-a-generation event.” These fires constitute significant new information that warrants preparation of a supplemental EIS.The rest of the letter is well worth a read as it outlines a range of related issues as Oregon grapples with the new normal undeniably enhanced by climate change.

Read the complete document HERE.

NATURAL GAS: LNG export projects face ‘uncertain’ future — report, dated October 6, 2020

Miranda Willson, E&E News reporter

A glut of natural gas supplies and the economic slowdown from the pandemic have created a “highly uncertain” outlook for planned liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facilities, according to a new report from an environmental nonprofit.

Ten proposed U.S. natural gas export terminals and expansion projects are delayed, and the status of another seven projects approved within the last 18 months is “unclear,” the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP) said in a report released yesterday.

U.S. LNG exports decreased by more than 50% this year, and about twice as many U.S. oil and gas producers have declared bankruptcy so far in 2020 than last year, EIP said. Given these trends, it is increasingly likely that some proposed projects won’t be built, the report said.

“Recent project delays indicate that the industry expects market conditions to remain unsupportive of future LNG exports,” EIP said.

LNG export terminals were already on shaky ground before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March, said Alexandra Shaykevich, research analyst at EIP.

“All of those preexisting problems in terms of low energy prices, the chronic oversupply of natural gas and the size of the LNG glut … have been significantly compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic,” Shaykevich said on a call with reporters.

Since some of the 17 planned LNG projects lack financing, regulators and companies could still reassess their need and consider their environmental costs, according to EIP.

The 17 delayed projects would emit up to 67 million tons of greenhouse gases annually, EIP said. That’s equivalent to the emissions released from 16 coal-fired power plants “operating around the clock for a year,” and it doesn’t include emissions from end-use consumption of the natural gas, Shaykevich said.

“The total emissions footprint of the natural gas industry is substantial and threatens to lock-in demand for fossil fuels while slowing the transition to renewables and other sustainable sources of energy,” the report said.

Many of the projects pose environmental justice concerns as well, as they have the potential to release local air pollutants that elevate the risk of asthma and other illnesses among nearby residents, EIP said. Thirty-eight percent of residents within 3 miles of proposed LNG facilities are people of color, and 39% are low-income residents, according to the report.

Residents in Port Arthur, Texas, a refining hub on the Gulf Coast that is the site of one proposed LNG terminal, are already subject to oil and gas industry pollution, said John Beard, president and CEO of the Port Arthur Community Action Network. It is not clear that residents have much to gain from additional projects, including LNG terminals, he said.

“One has to wonder, what’s the need and what’s the benefit?” Beard told reporters.

LNG facilities under development should be required to get new Clean Air Act permits considering the time that has passed since companies won approval, EIP said. Six of the projects received permits more than three years ago, even though projects must begin construction “within a reasonable time” under the Clean Air Act, said Eric Schaeffer, executive director of EIP.

“Clearly at this point, there’s no reason not to pull these permits given how saturated the market is already, given the long delays we’ve already experienced with these projects and the fact that they don’t seem to have secured the financing,” Schaeffer said.

Two energy policy professors not affiliated with EIP, however, criticized some of the report’s claims.

For example, the report does not account for emissions from coal-fired generation that could be avoided by LNG exports. Burning natural gas is less carbon-intensive than using coal.

Exporting LNG could reduce the need for a country such as China to build additional coal-fired power plants, said Ed Hirs, an energy economics professor at the University of Houston.

“They should be looking at what the LNG is a substitution for, and it’s pretty clear it’s a substitution away from coal and away from oil,” Hirs said.

The report also appears to disregard recent trends in LNG demand, said Erin Blanton, senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. While demand for U.S. LNG exports has declined since the beginning of the year, it has shown signs of recovery, as existing LNG terminals have seen increased use since July, Blanton said.

Some analysts predict terminals will be fully utilized by winter, Blanton said.

“I wouldn’t extrapolate from this year that there’s no future for U.S. LNG because of the pandemic in 2020,” she said.

Although energy markets have been in retreat because of the pandemic, U.S. LNG exporters processed nearly 8 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day as of yesterday, said Charlie Riedl, executive director for the Center for LNG. That’s up from deliveries of 4 billion cubic feet per day in June, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“As nations look to reduce emissions, improve air quality and spur economic growth, many will use natural gas and LNG to create a cleaner energy future,” Riedl said in an email.