This time a local permit set-back for JCEP

July 21, 2020

Good news! Here’s a press release from Crag Law Center that explains what happened and some of what this means. I want to add a little more context by way of giving kudos to the legal team that accomplished this.

The Crag Law Center and the LWV go way back. The LWVUS and LWVOR have filed two amicus briefs in support of plaintiffs in Juliana v. USA, the landmark climate lawsuit initiated in 2015 and is still ongoing. Crag’s Executive Director Courtney Johnson drafted both of those briefs for the Leagues. That in addition to work against JCEP.

Tonia Moro, who represented the Coos Bay Citizens for Renewables in the LUBA reversal, has been in the JCEP fight over the long haul, too. She was supported in this current work in part by a grant from the LWVOR, precisely because of her track record for getting things done and the understanding that receipt of local land use permits, including this one, are an essential part of the bigger effort to stop this project.

There’s way more to this very complex story, but we want to underscore Tonia’s and Courtney and her colleagues at Crag’s excellent work on behalf of the local, state, national, and global community, including to stop this massive project. If built, it would deal an enormous blow to Oregon’s goals and efforts to reduce GHG emissions and ensure environmental justice and cause irreparable damage to the natural and human environment across southern Oregon and in the Coos Bay Estuary and community.

UPDATE JULY 7, 2020. RECENT ARTICLE FROM KDRV NEWS 12.

dateline: June 2, 2020

As the State of Oregon is battling JCEP’s attempt to get FERC to declare that Oregon waived its Section 401 authority, making moot DEQ’s May 2019 denial of that essential permit, the EPA released its new rules on that section of the Clean Water Act yesterday. In other words, the Administration is lending a hand to get JCEP done in case FERC doesn’t do this additional job.

A congratulatory article in the Financial Times this morning said this: “The Trump administration has curbed US states’ power to veto energy infrastructure projects, drawing praise from fossil fuel industries for a move that could make it easier to build pipelines and export terminals across the country. The Environmental Protection Agency on Monday reinterpreted provisions in the federal Clean Water Act that state governors had used to stymie projects targeted by climate campaigners. . . . The state of Oregon blocked the Jordan Cove liquefied natural gas export terminal citing the provision. . . . Energy companies argued the states were abusing a clause in the water law to obstruct projects they opposed for other reasons. Andrew Wheeler, EPA administrator, said the agency was returning the certification process to its ‘original purpose, which is to review potential impacts that discharges from federally permitted projects may have on water resources, not to indefinitely delay or block critically important infrastructure.’”

It’s not clear yet whether Pembina will attempt to use the new regs to try to get JCEP to happen. It seems that JCEP might submit a new application for their 401 permit now under the new rules as a Plan B, but they also might wait and let their waiver claim to FERC play out first. If FERC grants their petition, Oregon (and community opponents of JCEP) may sue. If they reapply, the regular state permitting process will need to proceed. It’s unlikely DEQ will grant the permit because of the egregious adverse impacts, even under the new rules. And Governor Brown (and the LWVOR) commented in opposition to the proposed regs last fall (both attached), charging that they were unlawful misinterpretations of the Clean Water Act, as did any other states and environmental organizations. That route likely leads to court, as well.

dateline: May 27, 2020

NATURAL GAS: Ore. landowners sue over ‘indefensible’ export project

Arianna Skibell, E&E News reporter

A group of about 30 property owners has sued to block a proposed Oregon liquefied natural gas export terminal and corresponding pipeline that would cut across their land.

The landowners asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit on Friday to review the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s approval of the Jordan Cove LNG export project and the Pacific Connector Gas pipeline.

“We will do all we can to try and stop this incredible overreach and the blatant misuse of eminent domain to benefit special interests over public interest,” said Deb Evans, a challenger in the case.

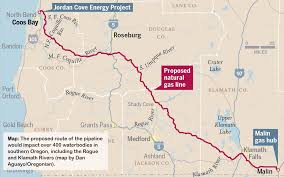

The $10 billion project, backed by the Canada-based Pembina Pipeline Corp., would include a 230-mile, 36-inch-diameter feeder pipeline that would run from a town along the Oregon-California border to a 200-acre natural gas liquefaction and export terminal at Coos Bay. The export hub would be the first on the West Coast, closer to energy-hungry Asian markets.

The oil and gas industry has been pushing for the development of LNG terminals to facilitate greater exports of gas as the fuel glut continues. The terminals liquefy gas by refrigerating it to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, which reduces its volume and allows it to be transported on ships. The Jordan Cove hub could liquefy up to 1.04 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day for export to Asia.

FERC approved the project in March and last week upheld its decision despite requests to reconsider from affected landowners, the state of Oregon, tribes, environmentalists and fishing interests (Greenwire, May 21).

David Bookbinder, chief counsel of the Niskanen Center, who is representing the landowners, said he’s confident the D.C. Circuit will rule in their favor.

The Jordan Cove project, he argues, does not pass the eminent domain test. While FERC can issue a certificate of public convenience and necessity, which grants eminent domain authority to developers, the project must demonstrably serve public interests.

Bookbinder said the D.C. Circuit made clear last year in City of Oberlin, Ohio, v. FERC that an export-only project doesn’t automatically meet this threshold. In that case, the court instructed FERC to take a second look at its rationale for approving the Nexus pipeline, which runs through Ohio and Michigan on its way to Canada (Energywire, Sept. 9, 2019).

“The law is you can’t count this,” he said.

Bookbinder will argue on behalf of landowners affected by the Jordan Cove project that a Canadian company selling Canadian gas likewise does not benefit the American public.

He also noted an absence of gas contracts for the project. In 2016, under the Obama administration, FERC rejected Jordan Cove because of concerns about consumer demand. Bookbinder said the project’s developers have not assuaged those fears.

“The idea that a company that has no customers will take U.S. property in order to ship Canadian gas to Japan is outrageous,” Bookbinder said. “That is indefensible in so many different ways.”

‘Landowners get thrown under the bus’

For the property owners involved, the court filing offers a glimmer of hope in what has been a 15-year saga.

The Jordan Cove project was proposed as a natural gas import facility in the early 2000s, when Evans and her husband, Ron Schaaf, bought their property. The project was changed to an export site when U.S. hydraulic fracturing operations significantly boosted domestic supplies.

“We were busy; our kids were in school. We followed it, but not super-close,” Evans said. “Then fracking came in, and the project disintegrated.”

In 2013, Jordan Cove’s developers filed a new application with FERC. Their bid was denied in 2016 following concerns about a lack of customers; falling property values; and harm to environmental resources that support timber, fishing and other local industries (Energywire, March 14, 2016).

“It’s the same landowners who have been affected by this for 15 years,” Schaaf said. “Landowners get thrown under the bus, and many landowners don’t have a lot of money. Not everyone has the opportunity to advocate for themselves.”

FERC Chairman Neil Chatterjee, a Republican, stressed that while Pembina has eminent domain authority to condemn private property for its pipeline, no construction on the pipeline or LNG terminal, including land clearing, can take place until the company has obtained the necessary permits — which is proving to be an uphill battle.

Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality denied the project’s water quality certification. The state Department of Land Conservation and Development rejected a permit because of the adverse effects the facility would have on coastal and critical habitats, as well as on endangered species. In February, it ruled that the project was not in line with the state’s coastal zone land use laws.

Pembina recently withdrew its application for a dredging permit when the Department of State Lands indicated that it was about to reject that application, as well.

Evans said she doesn’t understand why FERC would allow the pipeline developer to condemn her land while at the same time agreeing that no construction can begin without the requisite permits.

“Why would eminent domain be allowed before the conditions are met?” she asked.

‘FERC is delivering on its promise’

On a call with reporters after rejecting requests for rehearing on the project, Chatterjee said eminent domain is outside FERC’s jurisdiction.

“When it comes to eminent domain, we have no authority,” he said. “We’ve got expertise in how essential it is to siting pipelines.”

For landowners, Friday’s D.C. Circuit petition carries extra meaning. FERC’s swift rejection of the request for rehearing allowed landowners to seek recourse instead of hanging in legal limbo while pipeline construction moved forward.

“It’s a good example of Neil Chatterjee following up and delivering on his promises,” Bookbinder said. “FERC is delivering on its promise that it would not stop landowners from going to court.”

The commission has recently come under fire for issuing so-called tolling orders, which indefinitely extend the deadline for FERC to respond to landowner challenges while allowing pipeline construction to proceed.

FERC has issued a tolling order for every rehearing request filed over the past 12 years. Every case was then eventually denied. On average, 212 days — about seven months — passed between the time a landowner made a request for rehearing and when FERC ultimately denied it.

While Chatterjee has said his agency has addressed the issue, a case against FERC’s use of tolling orders is pending before the D.C. Circuit (Energywire, April 28).

Schaaf said he’s grateful that the landowners’ complaint over Jordan Cove can move forward.

“We understand owning property is a privilege and fighting for it is a privilege,” he said. “We’ll be in this until the end. We don’t know how it’s going to turn out.”

dateline: May 24, 2020

https://www.westernnaturalgas.org/post/openlettertogovernorbrown

dateline: May 22, 2020

1) Recall from last update that the State of Oregon (specifically four agencies) had filed a petition for Rehearing on FERC’s Order granting the two major federal authorizations JCEP needs to go forward. The article also mentioned that a coalition of around 30 organizations also filed a petition for Rehearing, but was not very specific. That petition included Niskanen Center, the law firm representing around 20 affected landowners, Sierra Club, and also for the interest of this group, the four local LWV that have been jointly opposing JCEP since their application. Yesterday, the FERC met and denied those petitions. I haven’t read the Order yet, but it includes some confusing language that we’ll probably need legal eyes to interpret. Hopefully, it doesn’t throw any problems in the direction of key petitioners. The Niskanen Center has already filed an appeal to the DC Circuit and the coalition’s attorney members are moving in that direction, as well.

2) JCEP has filed a Declaratory Order (roughly a petition), charging that the State of Oregon failed to action on the company’s Section 401 Water Quality Certification application within the one-year time limit specified in the Clean Water Act and thereby waived its authority to determine whether the Project would violate Oregon’s Water Quality Standards. The Department of Environmental Quality denied JCEP’s application in May 2019. A Section 401 permit is necessary for the Project to go forward, but the waiver would make the denial null. The State is working on a response. The deadline is June 4.

3) JCEP has appealed the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development (DLCD) Objection to the company’s Coastal Zone Management Act certification to the Secretary of Commerce, asking him to override the State’s decision. This is an allowable option in the event of an objection, but we have looked carefully at the rules governing under what circumstances the Secretary can legally perform an override and agree with the State and many others that the required circumstances don’t exist. The Oregon AG’s Office submitted the required Brief last Tuesday and we are now awaiting the next step. If an override occurs, this issue could wind up in court as well.

4) An outside, apparently well-funded national group (Consumer Energy Alliance) has created an “astroturf” (faux-grassroots) entity called the Western States and Tribal Natural Gas Initiative (WSTM) involving natural gas and LNG export proponents (e.g., western states’ local government officials, Chambers of Commerce, and some tribal groups) in the push for the JCEP. Expect to see a full-page ad in the Oregonian this Sunday, purporting to be a local and grassroots effort linking the construction of JCEP with means for economic recovery from COVID-19. News (start at 2:02:48 on the video) of this and other activities by CEA came via connections in Utah with concerns about fossil fuel development in the fracking fields there. More as this develops. As if Goliath wasn’t muscular enough already.

5) Finally, on the human side of this, here is a link to coverage of how this (the JCEP) pipeline project is affecting property owners whose land happens to lie on the proposed pipeline route. There’s a lot here. The blogs are excellent.